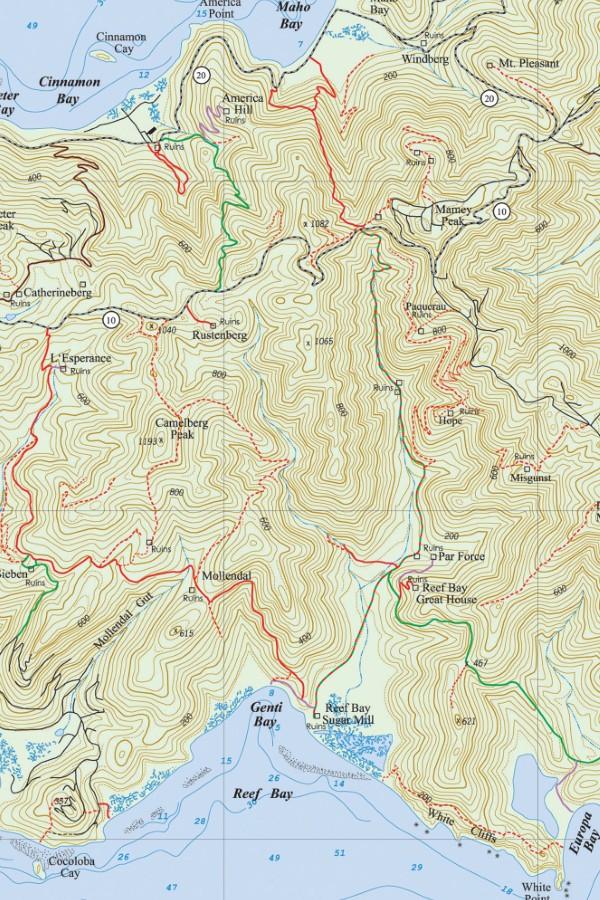

The Reef Bay Trail begins at Centerline Road, 4.9 miles east of Cruz Bay. The trail runs between Centerline Road and the ruins of the Reef Bay Sugar Factory near the beach at Genti Bay.

The well-maintained 2.4-mile trail descends 937 feet from the road to the floor of the Reef Bay Valley. The average hiking time is two hours downhill from Centerline Road to the beach.

You have two options when it comes to hiking this Virgin Islands National Park trail. You can go on a guided tour or plan your own hike.

The National Park Service offers guided hikes down the Reef Bay Trail. Transportation is provided from the National Park Visitors Center in Cruz Bay to the head of the trail.

An experienced Virgin Islands National Park Ranger will act as your guide. In addition to the Reef Bay Trail, the walk includes the spur trail to the petroglyphs and a visit to the Reef Bay Sugar Mill.

From the beach near the mill, you meet by a boat, which takes you back to Cruz Bay and allows you to avoid the more strenuous walk back up the trail. This popular activity is offered for a modest fee and is available by reservation only. Call the St. John National Park Service at (340) 776-6201 ext. 238.

Those making their own arrangements for this hike need to consider their transportation to the Reef Bay trailhead on Centerline Road and the method of return from the bottom of the trail.

The simplest procedure is to leave your vehicle in the parking area across from the trailhead on Centerline Road, walk down the trail, and then walk back up the way you came. Parking for four or five vehicles is available opposite the trail entrance.

No formal arrangements have to be made, so you can go whenever you want and with whomever you want if you’re visiting the US Virgin Islands.

However, the long, steep, uphill walk back is far more difficult than the descent. This should not be a problem for those in good physical condition who might even enjoy the challenge.

Make sure to pace yourself and bring plenty of water and bug spray. It might also be a good idea to plan a picnic either at the ancient petroglyphs or at the beach near the sugar factory.

A cooling swim at Genti or Little Reef Bay is another pleasant way to prepare for the walk up the valley. There are plenty of places within the Virgin Islands National Park that you can rest.

When planning your hike, make sure you have all of the necessary equipment with you, including proper clothing, water, sunblock, insect repellant, and a cell phone.

It’s also possible to exit the Reef Bay Valley without having to go back up the way you came. One good way to do this would be to make a loop using L’Esperance Road as a route back to Centerline Road.

A second option would be to take the Lameshur Bay Trail to Lameshur Bay and either arrange for transportation back to Reef Bay or walk to Salt Pond Bay and take the bus back.

The Reef Bay to Lameshur route involves backtracking about a mile from the Reef Bay Sugar Factory to reach the trail, then walk 1.5 miles with a rapid 467-foot elevation gain and subsequent descent in order to reach the road at Lameshur Bay.

This is no easier than returning uphill on the Reef Bay Trail, and it’s only recommended for those with high fitness levels. It’s necessary to pace yourself and to bring plenty of water.

Another alternative is to walk along the Reef Bay coast to the western end of the bay, where there is access to a road in Estate Fish Bay.

Transportation should be arranged on both sides of this hike, as it is a long way back to the Reef Bay trailhead, and hitchhiking is difficult on the infrequently traveled roads of Fish Bay.

Reef Bay Valley

The Reef Bay Valley, located on the south side of St. John, is a classic example of a beautiful geographical formation.

The steep and well-defined mountains that form the Reef Bay Valley are among the highest in St. John, and the valley follows the course of two stream beds, locally called guts.

The Reef Bay Gut begins at Mamey Mountain and runs down the center of the valley to Reef Bay. Parallel to the Reef Bay Gut on the western side of the valley is the Living Gut, also called the Rustenberg Gut, which begins near Centerline Road and meets at the lower levels of the valley.

A freshwater pool formed by the Living Gut provides the location of the ancient Taino rock carvings called the petroglyphs. You can also find a beautiful and vast waterfall around this area.

Reef Bay Trailhead

The Reef Bay trailhead begins at the bottom of the stone stairway on the southern side of Centerline Road.

Looking toward Centerline Road from the bottom of the stairs, you can see an old stone wall. This was once the retaining wall for the circular horse mill on the plantation ruins known as Old Works and is all that remains of the old estate, which was demolished during the construction of Centerline Road.

Until the end of the eighteenth century, people couldn’t travel all the way from east to west on what was then called Konge Vey (King’s Road) and which is now known as Centerline Rd or Route 10.

The road was divided in two by a deep gorge at the saddle of the Maho Bay Valley on the north and the Reef Bay Valley on the south. This gorge, called the defile, was so deep, its sides so steep, and the bottom so rugged that it was impassable by donkey cart or horseback.

The land bridge over the defile changed the dynamics of St. John as now deliveries from east of the defile could be sent to Cruz Bay overland, and since it was so much closer to St. Thomas, it became the favored port and the main town on St. John.

From Centerline Road to Josie Gut

The Reef Bay Trail roughly follows the course of the Reef Bay Gut, which drains the valley and flows downward toward the sea.

The top section of the trail descends steeply through the moist sub-tropical forest of Reef Bay’s upper valley, shaded by several varieties of large trees, including West Indian locust, sandbox, kapok, mammee apple, and mango. National Park Service information signs provide valuable information about the natural environment of the valley.

Flora Along The Trail

The first tree that you will pass, marked by a NPS sign, is a West Indian Locust. The sign reads: “West Indian Locust, (Hymenaea courbaril) Bean Family.

This tree is found throughout the West Indies and parts of Mexico and South America. The durable wood of this handsome tree is used for furniture, shipbuilding, crossties, and posts.

The tree exudes a useful gum resin. It produces large, dark, red seed pods containing several seeds surrounded by a strong-smelling, yellow pulp that gives this tree the local name of “stinking toe tree.” The pulp is edible and sweet tasting.

The holes you see in the bark are made by the yellow-bellied sapsucker to set a sticky, sap-laden trap for ants.

A beautiful old kapok tree grows just alongside the trail, identified by a National Park Service Information sign. The kapok is known by different names in different parts of the Caribbean. In the British Viring Islands, it’s called the silk cotton tree.

Because of its great size, its tendency to grow straight, and because the wood is soft and more easily worked using primitive stone tools, the kapok was chosen to make the great canoes used by the Taino to travel from island to island.

Slaves brought to the Caribbean often slept on mattresses and pillows stuffed with the fluffy silk cotton fiber from the kapok seedpods. Interestingly enough, this custom was often shunned by white planters and plantation overseers who believed that sleeping on kapok pillows brought about nightmares.

The Sandbox tree is another unusual tree found on the edge trail. It’s recognized by its many dark, pointed spines and smooth bark. The sharp spines along the trunk have caused it to be called monkey-no-climb. The white prickle, yellow prickle, and kapok have also been called monkey-no-climb for the same reason.

The origin of name sandbox tree comes from the use of seedpods as a desk accessory during the Victorian era. The ripe pods were collected just before they burst apart and were reinforced with glue to keep them together. People would then place sand in them, which was used to blot ink.

Jossie Gut Ruins

The Reef Bay Trail passes through the old Jossie Gut Estate about a half-mile from the trailhead at Centerline Road and runs right by the remains of the horse mill and the sugar factory.

The horse mill lies on a circular platform 65 feet in diameter. It’s supported on the lower side by a 16-foot high stone retaining wall, which has a small storage room built into it.

The upper side (on the other side of the trail) is cut into the hillside.

The sugar works at Jossie Gut further down the trail date back to the early 19th century. The estate was owned and operated by Hans Henrik Berg from the 1820s until his death in 1862.

The remains of the Jossie Gut sugar factory lie just below the horse mill. It was built almost entirely out of native stone, with the exception of bricks, used to line the doors and windows and the corners of the building.

The factory is T-shaped. The stem part of the T ends just three feet from the horse mill wall. This part of the factory was single-storied and housed the boiling house.

The firing trench can be seen on the back or downhill side of the wall. The top of the T contained the storage and curing rooms. The remains of two staircases can still be seen.

Jossie Gut is also significant for using a surface water collecting and distributing system that captured water from the gut utilizing a dam and a sluiceway and gutter that led to a cistern.

The remains of this simple but effective water works can be found on the upper side of the trail above the horse mill.

The walls and foundations of the structures found at Josie Gut were constructed using locally obtained stone, brain coral, and imported red and yellow bricks. These bricks, made in England and Germany, can be found in the ruins all over the island.

The story of how they ended up in the walls of a Caribbean sugar plantation provides some insight into the culture and morality of the time and place from which they came.

Brain coral was another important construction material. It was used primarily on arches and as cornerstones. Brain coral served this purpose well because when it’s first brought from the sea, it remains soft and can be cut easily with a saw to the size and shape needed. After the brain coral was shaped, it would be placed in the sun to dry, where it would become hard and rock-like.

Stone, already plentiful on the surface of the ground, was also uncovered during excavations for terraces, buildings, and roads.

Mortar was made from a mixture of lime, seashells, water, and molasses. The lime was fabricated locally by burning chunks of coral and seashells.

The framework and roofs of the buildings were made of wood. Many of the larger beams were made of the extremely hard and durable Lignum vitae, a tree that was once plentiful on St. John.

From Josie Gut to the Sea

After leaving the Josie Gut area, the trail becomes less steep, and the environment gradually changes from moist to dry forest, characterized by smaller trees and sparser shrubbery.

About one mile from Centerline Road, now well within the more gently sloped lower valley, the Reef Bay Trail passes by the remains of what was a small house, which was built around 1930. This section of the Reef Bay Valley is known as Estate Par Force.

The house alongside the trail was once owned by Miss Anna Marsh, who cultivated fruit trees and raised cattle. In those days, permission had to be granted by Miss Marsh in order to continue down the trail to the abandoned sugar mill or to the ancient petroglyphs.

The ruins of the Par Force Estate lie to the northeast of the Marsh House. A spur trail, the Par Force Estate House Trail, will take you to the ruins. The more adventurous may go into the bush behind the Marsh house and follow the gut north and up.

The ruins lie on the east side of the gut.

About 0.1 mile past the Anna Marsh house, you will come to the Petroglyph Trail, which will be on your right (heading west). The next trail intersection will be the Lameshur Bay Trail, which leads to the left (east) while the Reef Bay Trail continues straight. For information on the Lameshur Bay Trail.

Reef Bay

The Reef Bay Trail continues straight (south) on relatively flat terrain and leads to the partially restored Reef Bay sugar factory and the beach at Genti Bay.

Many citrus trees were planted along this section of the Reef Bay Trail, and some lime trees still remain. Two of these trees are growing right alongside the trail. If you find ripe limes, take a few back with you. They’re especially delicious and make excellent limeade.

In her book, Some True Tales and Legends About Caneel Bay, Trunk Bay and a Hundred and One Other Places on St. John, Charlotte Dean Stark remembers collecting fruit in Reef Bay:

‘There are cultivated orange trees there (at Estate Reef Bay), and once, to our joy, in 1948 or 1949, there was enough rain to produce a crop of five hundred oranges. They were exceptionally sweet and of fine flavor.”

As the trail nears the sea, it passes through a low-lying marshy area. The holes in the earth are land crab holes. This was once a popular place to gather these island delicacies.

Land crabs are now protected within the National Park boundaries, and hunting them is forbidden.

The Reef Bay Sugar Mill remains in extremely good condition. A visit here may increase your understanding of the sugar-making process and help you to imagine what life was like in days gone by.

A good way to start your tour of the factory is to begin at the horse mill. Horses, mules, or oxen walked in continuous circles to power the three rollers of the cane crusher in the center of the mill. A slave (or after 1848, a “worker”) on one side of the crusher fed bundles of cane into the rollers, and a worker on the other side would receive them.

He, in turn, would send the crushed stalks back through the rollers for further extraction of the cane juice. The cane juice then flowed down the trough to the boiling room. The leftover crushed cane stalks, called bagasse, were dried out and stored.

One side of the boiling room housed the boiling bench and the row of copper boiling pots where the cane juice would be boiled down into a wet raw sugar called muscovado. The fires were fed from the outside of the building. Bagasse would often be burned to provide heat for the boiling operation.

The muscovado would then be dried and packed into 1,000-pound barrels called hogsheads.

Behind the horse mill, about twenty yards inland from the Reef Bay beach, is the well-preserved above-ground grave of W.H. Marsh. His two daughters are buried nearby.

Another item of somewhat esoteric historical interest is the origin of the bathrooms located near the Reef Bay beach. The former island administrator and Park Ranger, Noble Samuels, took Ladybird Johnson on the Reef Bay Hike in the early 1960s.

Upon reaching the sugar factory at the end of the trail, the former First Lady asked Noble Samuels for the location of the bathrooms. The Park Ranger acknowledged the lack of these facilities and pointed to the bush as a possible alternative.

Ladybird Johnson later donated money for the construction of the bathrooms, which are there for your convenience today.

Brief History of the Reef Bay Valley

The first human inhabitants of Reef Bay were hunter-gatherers who arrived in St. John almost 3,000 years ago. These primitive peoples were conquered or replaced by a farming-oriented society who were the biological ancestors of the Tainos, the people who Columbus encountered on his voyage across the Atlantic.

The farmers, like the hunter-gatherers, migrated from the South American mainland and up the island chain of the Lesser Antilles arriving in St. John about 2,000 years ago.

When Columbus sailed past St. John in 1493, he reported the island to be uninhabited. The Tainos that lived on St. John may have already fled the island in the wake of Carib raids, or they may have gone into hiding at the approach of Columbus’ fleet, later to fall victim to the depredations visited upon them by the Spanish colonizers.

In the early sixteenth century, St. John was reported to be re-inhabited by Amerindians fleeing Spanish persecution in St. Croix and Puerto Rico. By 1550, the island appeared to have been totally uninhabited, and it remained that way for about 100 years.

Between 1671 and 1717, St. John was intermittently occupied by small groups of woodcutters, sailors, fishermen, and farmers.

St. John was officially colonized and settled by the Danes in 1718. By 1726, all of the lands in the Reef Bay Valley had been parceled out to form 12 plantations. At first, these estates were devoted to a variety of agricultural endeavors such as cotton, cocoa, coffee, ground provisions (yams, yucca, sweet potato taro, corn, etc.), and the raising of stock animals as well as to the production of sugarcane.

By the later part of the eighteenth century, the 12 plantations were consolidated into five, and sugar became the dominant crop in the valley. Only Little Reef Bay never switched to sugar, growing some cotton but primarily concentrating on ground provisions and animals that were sold to the neighboring plantations.

Although much of the land was cleared for agricultural purposes, a large portion of the valley was left in its natural state. The least disturbed areas of the valley are the western side of the Reef Bay Gut and the mountain spur between White Point and Bordeaux Peak.

By the end of the eighteenth century, when sugar production was at its peak and the population of the valley was at its greatest (300), about half of Reef Bay Valley was classified as woodland.

After the abolition of slavery in the Danish West Indies, the sugar industry on St. John began to collapse. Most of the sugar plantations on St. John were sold, and their new owners switched to cattle raising or provision farming. The owners of Reef Bay, however, decided to continue the sugar operation.

To make the process more economically feasible, they installed a steam engine to power the rollers. This, they felt, would solve the problems associated with the slowness of animal power.

At the perimeter of the horse mill, next to one of the factory walls, is the steam-powered sugarcane crusher. The steam engine, built in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1861 by the W.A. McOnie Co., is located in the room alongside the rollers. This room was constructed especially to house the steam engine after it was put together and installed.

The sugar operation here did not proceed smoothly. The soil on the sugar plantations became depleted of nutrients, and the sugar crops became smaller and smaller. Moreover, the introduction of sugar beets in Europe and in the United States provided great competition and lowered sugar prices.

Reef Bay Estate and Estate Adrian, which also converted to steam power, were the last operating sugar mills on the island.

In the nineteenth century, agriculture in the Reef Bay Valley began to decline. By 1915, only Par Force and Little Reef Bay in the lower valley were still active, but with only ten acres planted in sugar. Otherwise, the plantations were devoted to cattle and other livestock, coconuts, fruit trees, and ground provisions.

In 1955, much of Reef Bay was sold to Rockefeller’s Jackson Hole Preserve Inc., which transferred the land to the National Park.

Today, most of the Reef Bay Valley, with the exception of some parcels of private property called “inholdings,” is the property of the National Park.