The 0.7-mile Tektite Trail leads up through the dry forest and connects with the old Tektite Road, which was constructed to support the Tektite Project (more on that down below). The trail then follows the ridgeline over three hills and leads to Beehive Cove. Along the way are spur trails to Cabritte Horn point and to the shoreline of Great Lameshur Bay. This is not an official Park trail.

The trail begins 60 feet west of the top of the steep concrete road leading down to Lameshur Bay, at the beginning of which are the remains of an old gate.

The trail rises steeply through dry forest vegetation. Beginning at elevation 193 and rising to 354, there is an ascent of 161 feet over a relatively short distance, so pace yourself accordingly.

At the top of the hill where the trail meets the remains of an old bulldozed road and the ruins of a stone structure.

You will be rewarded with beautiful views and refreshing tradewinds to cool you off after the steep, sunny climb. The trail continues over the ridge of the hill and begins a gentle decent leading to a grassy area with views to the east, south, and west.

The first fork to the left descends through a grassy area to Cabritte Horn Point. Here you can enjoy spectacular views of the southeast coast of St. John and, on clear days, St. Croix to the south.

The brisk trade winds carry the smells of Maran and frangipani. Look for barrel cacti with their edible fruits and wild orchids, which can be found growing in the grass, rocks, cactus branches, and trees.

Cabritte Horn Point is also an excellent place to observe sea birds like pelicans, frigate birds, gulls and boobies.

The Tektite Trail leads to a deep gorge with sheer rock walls descending to the sea. It’s so narrow you can easily jump over it, although you don’t have to since the trail leads around it.

Returning to the main trail, now more obviously a bulldozed road, you begin a descent with more great views to the west. From several vantage points on the trail, you can look down onto Beehive Cove, the site of the Tektite project, as well as one of the best snorkeling areas on St. John.

A short spur to the right, marked by an arrow painted on a rock, leads down to the Lameshur shoreline. From here, you can scramble over the rocks on the coastline to the beach at Donkey Cove and then on to Great Lameshur Bay and the South Shore Road.

The main trail continues to a knoll overlooking the rocky coast of Beehive Cove. From the overlook, the trail continues to a point where you can scramble down to the sea.

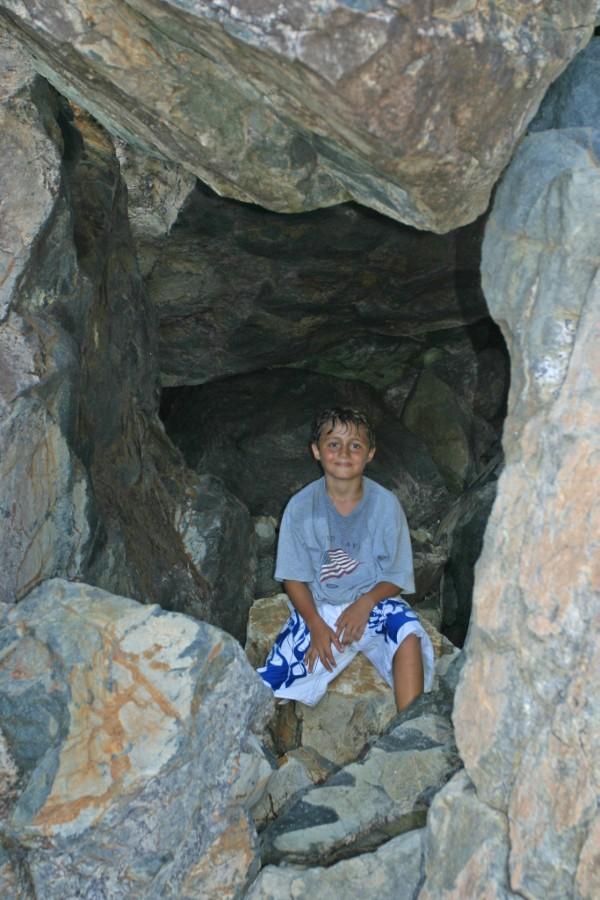

Near the sea, there is a small cave in which the interior is lined in most parts by beautiful quartz formations.

The Tektite snorkel area is just offshore, but this is not a convenient place to enter the water.

Here is some information on the Tektite Project, which is how the Tektite Trail got its name.

The Tektite Project was conducted in 1969 in a cooperative effort by the U.S. Department of the Interior, the U.S. Navy, NASA and the General Electric Co. The purpose of the study was to investigate the effects on human beings of living and working underwater for prolonged periods of time.

The name of the project, Tektite, comes from a glassy meteorite that can be found on the sea bottom.

An underwater habitat, which was built by GE and originally designed to be the model for the orbiting skylab, was placed on concrete footings 50 feet below the surface of Beehive Cove. It consisted of two eighteen-foot high towers joined together by a passageway.

Inside the towers were four circular rooms twelve feet in diameter. There was also a room, which served as a galley and a bunkhouse, a laboratory, and an engine room. The habitat was equipped with a hot shower, a fully equipped kitchen, blue window curtains, a radio and a television.

A room on the lowest level called the wet room was where the divers could enter and leave the habitat through a hatch in the floor that always stayed open.

The four aquanauts, Ed Clifton, Conrad Mahnken, Richard Waller and John VanDerwalker, who took part in the first Tektite Project lived under constant surveillance by cameras and microphones.

They often slept monitored by electroencephalograms and electrocardiograms to monitor their heart rates, brain waves, and sleep patterns.

The project lasted for 58 days and the men set a world record for time spent underwater, breaking the old record of 30 days held by astronaut Scott Carpenter in the Sea Lab II Habitat.