Snorkelers exploring the underwater wonderland awaiting just off the St. John coast will be treated to a vast new world of undersea delights. On these pages, we present interesting sea creatures that you may encounter on your snorkeling expeditions.

Algae

Anemones

This anemone pictured here is called an Orange Ball Corallmorph (Pseudocorynactis caribbeorum) They are usually found in depths of about 20 -80 feet and have one to two-inch-long tentacles. They inhabit coral reefs and sandy areas close to the reef. They quickly retract their tentacles if disturbed.

Angelfish

Angelfish have tall thin bodies, can turn quickly, swim backward, and maneuver themselves into small cracks in the coral reef in order to find the invertebrates and marine algae that serve as their main diet.

Balloonfish

Balloonfish (Diodon holocanthus), sometimes called long-spine pufferfish, have big eyes, and long spines and inflate like a balloon if threatened.

Great Barracuda

Barracudas can usually be found near the surface. Look for juveniles in mangrove forests, estuaries, and shallow sheltered inner reef areas. Adults can grow to be as much as four to six feet long.

The most important thing to remember here is that despite the barracuda’s ugly and fearsome appearance, unprovoked attacks on humans are extremely rare. They will often follow you around the reef, opening and closing their mouth to display their big sharp teeth, but not to worry, they are just curious and don’t intend to attack you.

Black Durgon

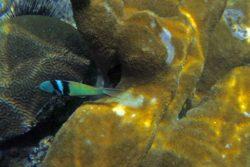

Blenny

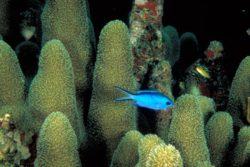

Blue Chromis

The Blue Chromis is in the damselfish family. They are commonly seen swimming in mid-water above the coral tops.

Blue Tang

The blue tang is important for the coral reef community because it eats algae off of rocks and corals, keeping the substrate clean and available for coral formation and keeping algae from smothering the coral.

Spotted Trunkfish

Honeycomb Cowfish

Butterflyfish

Chiton

Chitons, also called sea cradles, are mollusks found adhering to rocks that have a calcareous plate covering their mantle.

Conch

When I first came to St. John, grocery store pickings were sparse. It was way better to go out and catch you own dinner. In those days, if you didn’t have any luck catching fish or diving lobsters, you knew you could always get a conch.

They were very plentiful and easy to get then, just lying there in the seagrass on the bottom of warm, clear, shallow bays. What’s more, they move so slowly that, unlike fish or lobster, they can’t get away from you.

If the water was shallow enough, you could just reach down and pick them up. In slightly deeper water, all you would need was snorkel gear and a sack. In no time at all, you would be on your way to a delicious and healthy dinner of conch salad, conch stew, or conch in butter sauce.

It is easy to understand why conch was such an important resource to St. Johnians, beginning with the first inhabitants who arrived some 3,000 years ago. Conch meat is an excellent source of nutrition, high in protein and low in fat, not to mention its aphrodisiac qualities.

Corals

The orange cup coral is a brightly colored orange coral with flower-like yellow tentacles that extend at night or in areas of low light.

Although the orange cup coral is a hard coral, it’s not a reef-building coral. Also, unlike other corals, the cup coral does not depend on the symbiotic algae, which shares it’s photosynthesis-created food with the coral animal. Because of this, the cup coral can grow in dark places such as shaded walls, caves, and underneath overhanging ledges.

I first noticed orange cup corals on the walls of a rocky indentation on the Tektite snorkel and again on the walls of the caves at Norman Island. Now I see them elsewhere, even on the Trunk Bay Underwater Trail.

Cup corals do not seem to be a major problem here in the Virgin Islands as they seem to prefer the darker areas that other corals don’t like, and I’ve not seen any great proliferation in all the years that I have been snorkeling around the Virgin Islands.

They are, however, a problem in the Gulf of Mexico, where they tend to crowd out other native coral and sponge species. They especially like oil rig platforms where hundreds of thousands of colonies may be found attached to a platform.

Pillar Coral is a hard coral which is usually found on flat or slightly sloping sea floors in depths of between one and 65 feet. They can grow as large as 8 feet tall. Their polyps, which are used for trapping nutrients, are usually extended during the daytime.

Crabs

This unusual crab was photographed at Maho Bay. It’s a flame box crab that inhabits the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and the eastern seaboard of the United States. The flame box crab lives in sand flats and coral rubble with sandy areas. It is shy and buries itself in the sand when they see a diver approaching.

I found this crab in shallow water at Trunk Bay. Like the Puerto Rican sand crab, it buries itself in the sand and hides there.

Dolphin

Eels

Moray eels hide in holes in the reef during the day. They sometimes can be seen sticking their heads out of their hole, constantly opening and closing their mouths. They do this not to scare people but to pump water through their gills in order to breathe. At night they come out of their holes and search for food on the reef.

Scrawled Filefish

Fry

The tiny schooling fish that we call fry may be several different species, including silversides, herrings, anchovies, and scad.

Glassy Sweeper

Marine Worms

Feather duster worms are a type of tube worm. They attach themselves to the reef by a hard-shelled tube. Their colorful feathery tentacles that make them look like underwater feather dusters serve to filter nutrients from the water. When threatened, they quickly retreat into their tubes.

The bearded fireworm is a slow creature and is not considered a threat to humans unless touched by a careless swimmer. The bristles, when flared, can penetrate human skin, injecting a powerful neurotoxin and producing intense irritation and a painful burning sensation around the area of contact.

The sting can also lead to nausea and dizziness. This sensation lasts up to a few hours, but a painful tingling can continue to be felt around the area of contact. In the case of accidental contact, the application and removal of adhesive tape will help remove the spines; applying isopropanol to the area may help alleviate the pain.

Nassau Grouper

The Nassau Grouper is found on coral reefs. They used to be more plentiful and are now a protected species. When threatened, they retreat into holes or under ledges.

Grunts

Red Hind

Jacks

The bar jack is commonly found swimming over and around reefs or near beaches, often seen swimming above rays. It’s an efficient predator eating small fish, shrimp and squid. Although the bar jack is known to carry the fish poison ciguatera, it is generally thought to be considered a good-eating fish in most parts, but not in the U.S Virgin Islands, where most reported cases of the illness can be traced back to this single species.

Horse-eye jacks are strong-swimming predators that feed on small fishes, shrimps, and other invertebrates. The horse-eye jack often swims in schools and may mix with other species of jacks, notably the similar-looking crevalle jack.

Jellyfish

The moon jellyfish is the most commonly found jellyfish in St. John waters. It feeds mostly on plankton. They can propel themselves to a limited degree, but, by and large, they drift about with the currents.

The moon jellyfish can produce a mild sting in sensitive individuals, but most divers and snorkelers do not feel anything upon contact with their tentacles.

Most jellyfish swim around with their head up and tentacles down, but the Cassiopea spends most of its time with its head down, resting on the sea floor and with its tentacles extended upward, hence the name, upside-down jellyfish.

The Cassiopea can give divers a mild sting, which can be very itchy.

You’ll need to look carefully to see the translucent jellyfish in the above photo, but seeing it in the water is even more difficult. It has a dome-shaped head and four tentacles. It’s a sea wasp. It stings hard, and it’s hard to avoid. If you are unfortunate enough to get stung, pour vinegar on the affected area and, in severe cases, seek medical attention.

Lionfish

The lionfish is an invasive newcomer to the Caribbean. With its venomous spines that protect it from predation, voracious appetite, and skill as a predator, the lionfish has become a threat to the ecology of our coral reef community.

Caribbean Spiny Lobsters

The lobsters hide in holes and recesses in the reef during the day and forage in the open at night.

Cero Mackerel

Needlefish

Octopus

Parrotfish

Parrotfish are one of the most common species found on St. John reefs. They are extremely colorful and have fused teeth that look like a parrot’s beak. They swim using their pectoral fins.

The parrotfish in the photo has made a bag out of secreted mucus bubbles In, which it will then spend the night.

Reef grazing fish, such as parrotfish, produce a significant amount of the sand found on our beaches. Parrotfish exist on a diet of algae, which scrape off the surface of coral rock with their beak.

They then grind this coral and algae mixture to a fine powder. The algae covering the coral are absorbed as food. The coral rock passes through their digestive tracts and is excreted in the form of sand.

Snorkelers will frequently observe this process if they watch the parrotfish for a few minutes. A supermale parrotfish is one that began life as a female and later changed to a colorful supermale.

Ordinary male parrotfish spawn with females in groups of other males, while the supermale gets to spawn with an individual female or even with several females.

Pompano

Porcupinefish

The porcupinefish can usually be found lurking around cave entrances and will quickly retreat inside when approached. They will then peer out from the opening of the cave. When threatened, the porcupinefish inflates, and its long spines become erect.

Queen Triggerfish

Locally the Queen Triggerfish is known as Old Wife

Rays

Southern stingrays are commonly found in St. John waters in sandy areas, seagrass beds, and around reefs.

They are usually between three and four feet long but can grow to be as long as five and a half feet.

The southern stingray often lies on the bottom, covering itself with sand by flapping its large pectoral fins. This serves to protect it from predators and from the rays of the sun.

Because these stingrays can be so well camouflaged and because their sting can be so painful, it is a good idea to shuffle your feet (the sting ray shuffle) when in areas where stingrays are abundant, especially if in murky waters. In this way, the stingray will be alerted and will get out of your way.

Because the sting ray’s gills are located on the underside of its body. When lying in the sand, it uses the two holes near its eyes to breathe.

Manta rays can leap high above the surface of the water using the strength of their powerful wings. They have short tails without the stinging spines found in the tails of many other species of rays. Their diet consists of plankton, small fish, and small crustaceans.

Remora (Sharksucker)

Sand Diver

Sargassum Seaweed

Sea Cucumber

The sea cucumber belongs to the phylum Echinodermata, the same as the starfish. Although it hard to tell the difference, by definition, the mouth is in the front and the anus in the rear.

Sea Fans

Seagrass

Sea Turtles

Sea turtles are almost invariably a source of joy and excitement to the swimmers, snorkelers, and divers fortunate enough to happen upon these gentle and magnificent creatures. Two species, the green turtle and the hawksbill turtle, are commonly found around the Virgin Islands.

Green turtles are vegetarians and can usually be found grazing the seagrass beds in bays such as Maho, Francis, and Leinster bays.

Hawksbill Turtles have a distinctive hawk-like beak and are usually found around reefs where they hunt crabs, fish, and snails or use their sharp bill to scrape sponges, tube worms, and encrusting organisms off rocks and coral.

The giant leatherback turtle also inhabits our waters, but its almost extinct and rarely seen. The leatherback can grow to as much as eight feet in length and weigh over 1000 pounds. Leatherbacks are so-named because, instead of having a hard shell like other sea turtles, their backs are protected by layers of leather-like plates.

Leatherbacks live in deep water and subsist on a diet of jellyfish. A major threat to the leatherback comes in the form of improperly disposed plastic bags, which the leatherback may easily mistake for a jellyfish.

Sea turtles have been in existence for about 150 million years, inhabiting the tropical and subtropical seas of the world.

Even though these large reptiles spend almost all their life in the sea, they are air breathers. They hold their breath just like we do when we dive without tanks. Fortunately for sea turtles, they can hold their breath much longer than we can.

They are excellent swimmers, possessing large flippers that can propel their streamlined bodies through the water quickly and gracefully.

Instead of teeth, sea turtles have a beak like a bird (like a hawk in the case of the hawksbill turtle.) Sea turtles have no ears, which is probably just as well for creatures that spend their whole life diving.

They can still hear, though, accomplishing this through the use of eardrums that are conveniently covered with skin. Sea turtles have a keen sense of sight while they are under the water but are quite nearsighted when they stick their heads out of the water for their breath of air. The turtles also have an excellent sense of smell, which also functions best while they are submerged.

The female sea turtle comes ashore on secluded beaches at night to lay her eggs. She then covers the eggs up with sand and does her best to cover up any traces of her nocturnal activities. The mother turtle returns to the sea while the eggs incubate, a process that takes about eight weeks.

When the eggs hatch, the baby turtles dig their way out of the sand and crawl slowly towards the sea. They are very vulnerable at this time. The tiny turtles are easy prey.

Moreover they must avoid pitfalls such as getting trapped in holes in the sand, tangled up in seaweed, or having their way blocked by trash or other debris. They must reach the sea before the light of day exposes them to keen-eyed sea birds, mongooses, dogs and the baking hot tropical sun.

No one knows for certain what the hatchlings do next, but many scientists believe that the hatchlings then head out for the calm waters of the Sargasso Sea, which lies between the West Indies and the Azores in the middle of the Atlantic.

Here they drift about hidden amidst the plentiful sargassum seaweed until they grow large enough to avoid most predators. The turtles then begin their long journey back to the beach where they were born. When the female reaches sexual maturity, sometime between 15 and 50 years, depending on the species, she will lay her eggs on that beach.

The hawksbill, green, and leatherback turtles are all listed as federally endangered species. Overfishing and the commercial exploitation of hawksbills for tortoiseshell products such as combs, hair barrettes, eyeglasses, picture frames, and boxes have taken their toll on a once thriving population.

Sea turtles also face other serious problems. More and more beaches are being developed, rendering them unsuitable for turtle nesting.

Development also leads to an increase in the dog population. This is a problem because dogs are adept at finding and digging up turtle eggs. Furthermore, it has been shown that mongooses do not instinctively hunt turtle eggs but begin to do so after observing dogs engaged in this activity.

The awe and fascination that we experience upon an encounter with the sea turtle was shared by the cultures that inhabited these islands before us. To the spiritually evolved Taino people of the Caribbean, the turtle symbolized the ancestral mother and was a prominent feature in their religious art.

This majestic and peaceful being cannot be allowed to become extinct. We must remember that we share our environment with all of God’s creatures, and it is our responsibility to preserve and protect our unique heritage.

Sea Urchins

Sergeant Major

Sharks

Sharks and rays have skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone. They have small hard scales, which gives their skin a sandpaper feel to the touch.

While most sharks have lost their ability to pump water over through their gills and must remain in motion throughout their lives, the nurse shark is one of two species of sharks that has retained this ability and can lie at rest. The other species with this ability is the lemon shark.

Nurse sharks mostly eat marine invertebrates such as lobsters, shrimp and sea urchins. They capture their prey by their ability to create a strong suction through their small mouths and large throat cavities, which has led to their name, “nurse sharks.”

Lemon sharks get their name because many of them have a yellowish color. Like nurse sharks, they do not have to remain in motion to pass water through their gills.

Blacktip sharks are so-named because of the black coloring on the tops of their fins.

Banded Coral Shrimp

King Helmet

Atlantic Tritons Trumpet

A predatory sea snail that likes to eat starfish

Flamingo Tongue Snail

The bright orange-yellow color and black designs are not part of the flamingo tongue snail’s shell but rather a mantle tissue covering the shell.

Yellowtail Snapper

Gray Snapper

Glasseye Snapper

Mahogany Snapper

Caribbean Reef Squid

Caribbean Reef Squid, Sepioteuthis sepiodea, are found in shallow waters around reefs and seagrass beds.

Spotted Drum

Longspine Squirrelfish

Squirrelfish are commonly seen fish on St. John reefs. They prefer shaded areas close to the bottom.

Starfish

This starfish is called a Cushion Sea Star or Asteroid. They have five arms, which can regenerate if broken off. Occasionally a new starfish can develop from a broken off arm. The mouth is on the bottom and the anus is on top. Some sea stars have the ability to stick their stomachs outside their moths and put it around their prey (often a conch) and digest it from the outside before returning their (now full) stomach to where it belongs.

Tarpon

Tarpons are usually found in inshore areas and feed on small fish and crustaceans. They can fill their swim with air and absorb oxygen from it, enabling them to breathe air at the surface.

Trumpetfish

Tunicates

West Indian Top Shell (Whelk)

Whelks can be found adhered to rocks at the waterline or submerged. They are rumored to be an aphrodisiac and are an island delicacy traditionally prepared and sold during carnival time.

Hermit Crabs often use whelk shells for their home.

Wrasse